Title: A circumbinary protoplanetary disk in a polar configuration

Authors: Grant M. Kennedy, Luca Matrà, Stefano Facchini, Julien Milli, Olja Panić, Daniel Price, David J. Wilner, Mark C. Wyatt & Ben M. Yelverton

First Author’s Institution: Department of Physics & Centre for Exoplanets and Habitability, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

Status: Published in Nature Astronomy, closed access

Binary stars are a common outcome of star formation, yet most of what we know about planet formation comes from studies of disks around single stars. In fact, almost all of the “pretty pictures” of protoplanetary disks you have seen are around single stars (with at least one notable exception). In the simplest case, the rotation of the disk, host stars, and their orbits would all be aligned since rotation on small scales is inherited from the bulk rotation of the parent cloud. Yet, we have seen planets which go against this idea, usually indicating that something interesting is going on. Today’s bite presents the first observations of a disk in exactly the opposite configuration: a disk in a polar orientation around a young binary star system.

Disks are a common side effect of star formation (even around binary stars) due to conservation of angular momentum. These disks of gas and dust are the birthplaces of planets. The high densities allow dust to grow into planets and potentially start accreting gas. While most of the time the rotation of the disk tends to be aligned with that of the star, it is possible for the two to become misaligned. Orbital dynamics tells us that if the now misaligned disk is around a binary star it will precess just like a spinning top (i.e. the vector of its angular momentum will rotate). An interesting aspect of the dynamics is that this precession has two stable configurations. If the misalignment is small, the precession is around the binary angular momentum vector (pointing out of the plane of their orbit), but for large misalignments the precession is around the binary’s pericenter direction (the vector through the binary orbit’s major axis). This second scenario would result in a disk in a stable polar orbit, which is exactly what was observed around HD 98800.

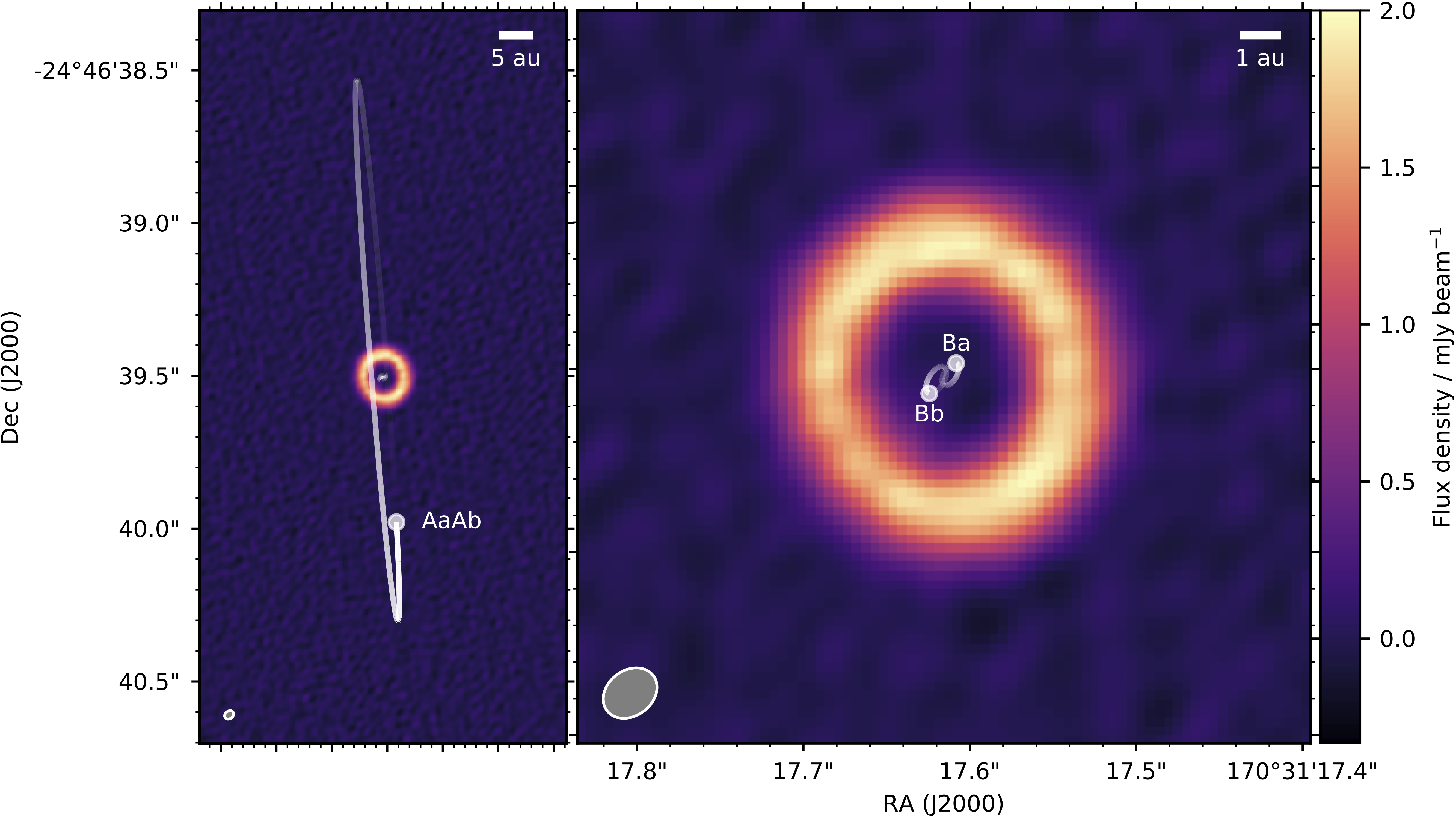

HD 98800 is actually not just a binary, it is a hierarchical quadruple system. In other words, it consists of two pairs of binary stars that orbit each other. Each binary is labeled with a capital letter (A or B) while each star in the binary is labeled with a lower case letter (a or b). The authors used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to observe thermal emission from dust (Figure 1) and line emission from carbon monoxide gas (Figure 2) coming from the disk. As shown in Figure 1, the disk is around the B system, while the A system is on a wide, long period orbit. They fit a simple model to the observations to determine the disk orientation, size, and structure.

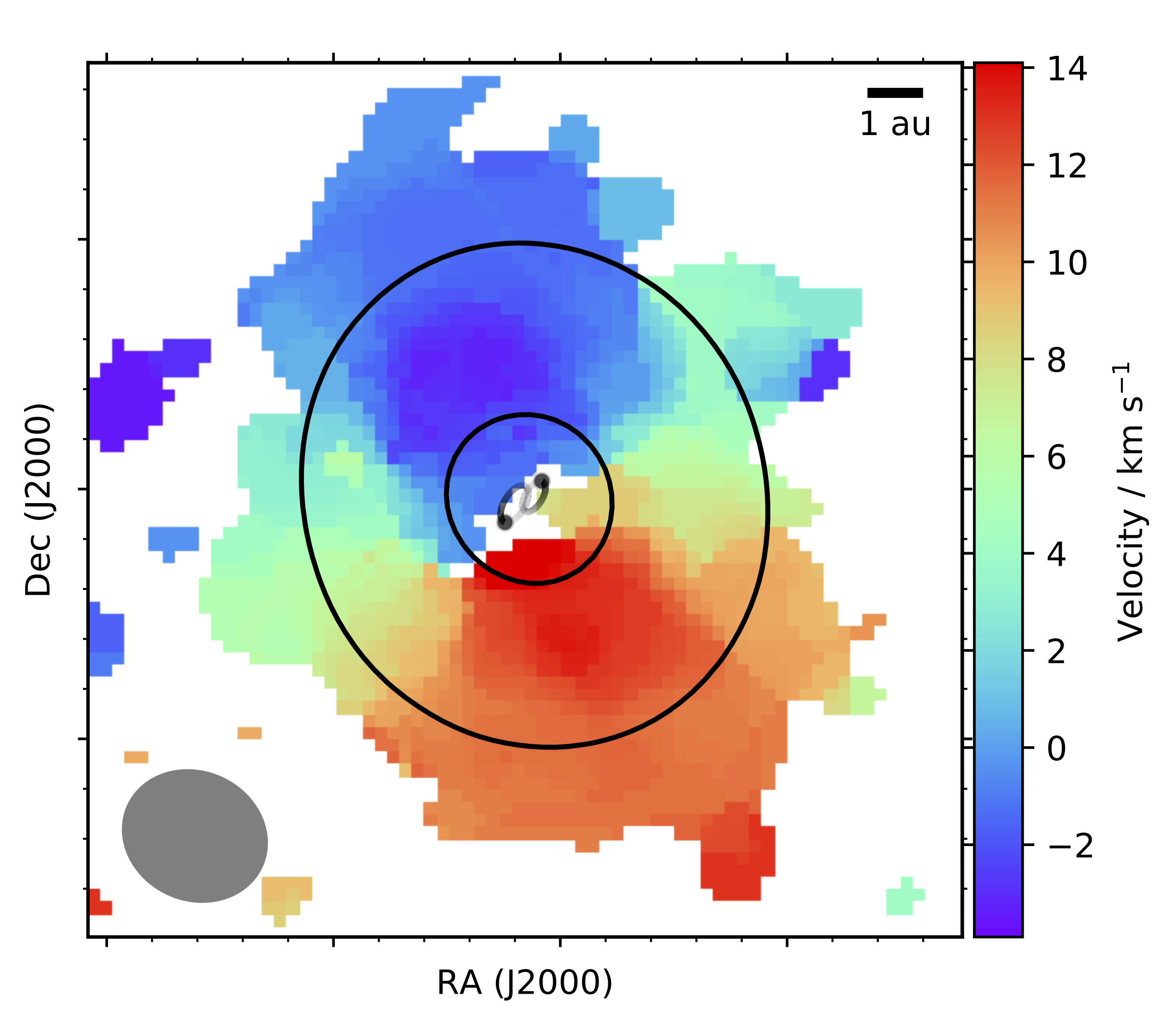

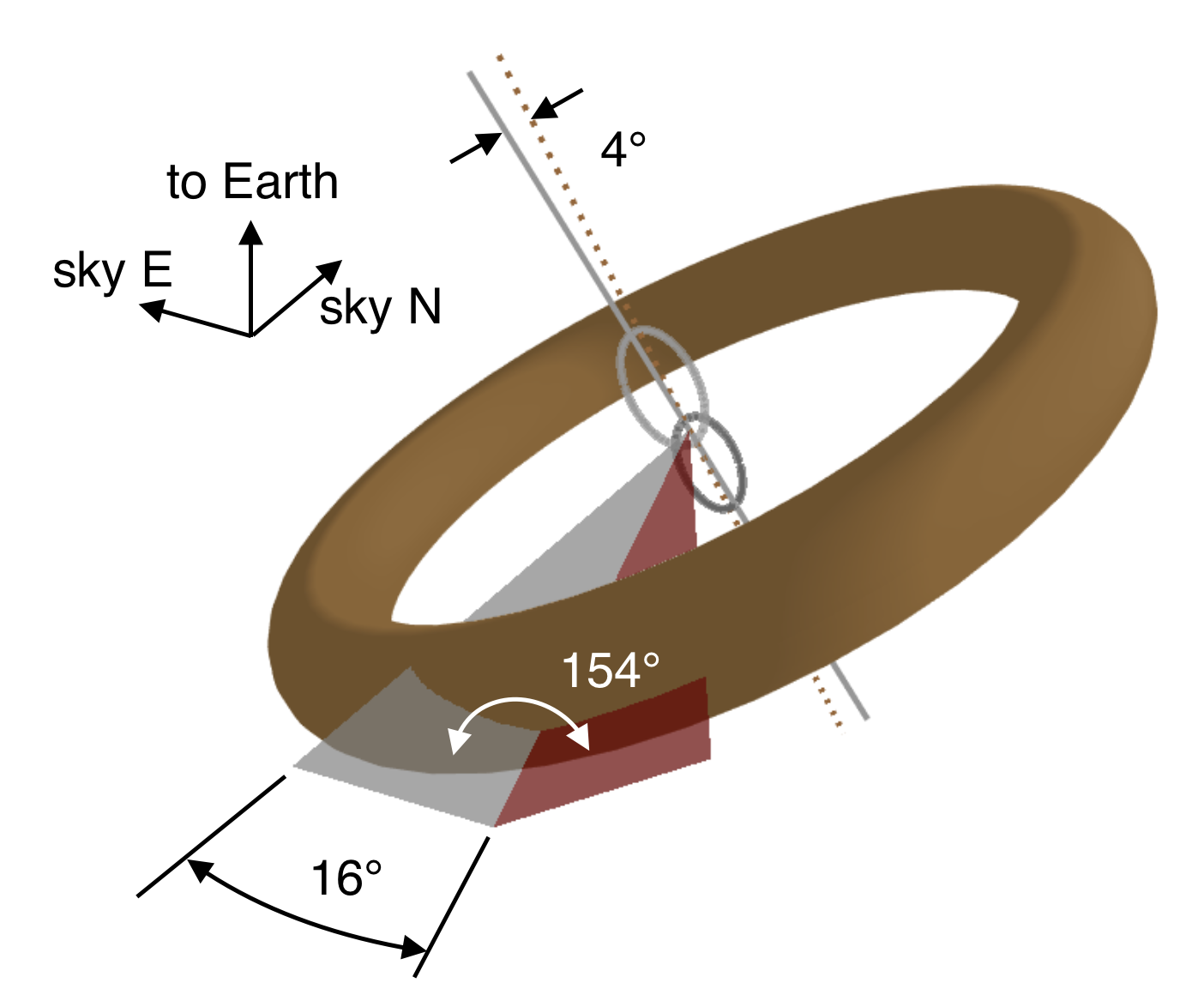

Since we can only see the two dimensional projection of the disk on the sky there is some degeneracy in the orientation of the disk. Figure 2 shows that the south side of the disk is rotating away from Earth while the north is rotating toward Earth. However, we do not know if the east or west side is closer to us. The best fit model indicates that the two possible inclinations of the plane of the disk are ~26° out of the plane of the sky (toward or away from Earth). These two orientations are 4° and 48° away from the polar configuration. Since the disk is around a binary, the nearly polar configuration is much more likely than the orientation about halfway between polar and aligned. The authors ran dynamical simulations to demonstrate this. The binary quickly (within several hundred years) reoriented the 48° moderately misaligned case into the polar configuration while the polar configuration was stable. Figure 3 shows a cartoon of the most likely orientation of the disk.

So how did this thing form? Two possibilities are that gas with slightly different angular momentum fell onto the disk from the parent cloud or there was some interaction with another star. It is possible that the culprit stuck around after the interaction and is now the A binary in this quadruple system. It is even possible that this interaction could have destroyed a disk around A. And why is this system so interesting? Theory told us that systems like this should exist, and we finally found one! Now the question will be if the numbers match our predictions. Also, this disk is similar to disks around single stars in that it shows signs of grain growth. This is the first step of planet formation, converting micron-sized dust into millimeter- and centimeter-sized pebbles. If planets were to form in this disk they would definitely have an interesting day-night cycle!

Read the origional post at astrobites.org.