Title: Upper limits on protolunar disc masses using ALMA observations of directly-imaged exoplanets

Authors: Sebastián Pérez, Sebastián Marino, Simon Casassus, Clément Baruteau, Alice Zurlo, Christian Flores, & Gael Chauvin

First Author’s Institution: Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Santiago

Status: Accepted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, closed access

Disks of gas and dust around young stars are fairly common; they are the birthplaces of planetary systems, hence the term protoplanetary disk. In the past few years, astronomers have used the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) to image these circumstellar disks and even catch planets forming within them. But the giant planets in our solar system also have systems of moons. How do they form? Most likely in a similar process by which the planets themselves formed, though in a circumplanetary disk (or protolunar) rather than a circumstellar disk (or protoplanetary). Today’s paper combines new and old observations of young giant planets that looked for, but failed to detect, these circumplanetary disks in order to constrain the timescale of moon formation.

The moon systems around the giant planets in our own solar system are surprisingly similar to each other, despite a wide range in mass and semi major axis. Excluding captured moons which did not form together with the planet, all the moons are close to orbiting in the same plane as the host planet’s equator (similar to how the planets in the solar system orbit aligned with the sun’s equatorial plane) and the total mass of the moon systems all are ~10-4 times the mass of the central planet. This even holds true for Uranus which is flipped on its side, though Neptune is an outlier (due to it’s late capture of Triton which likely disrupted the system). This is also similar to compact rocky planetary systems around low-mass stars such as Trappist-1, suggesting common formation processes.

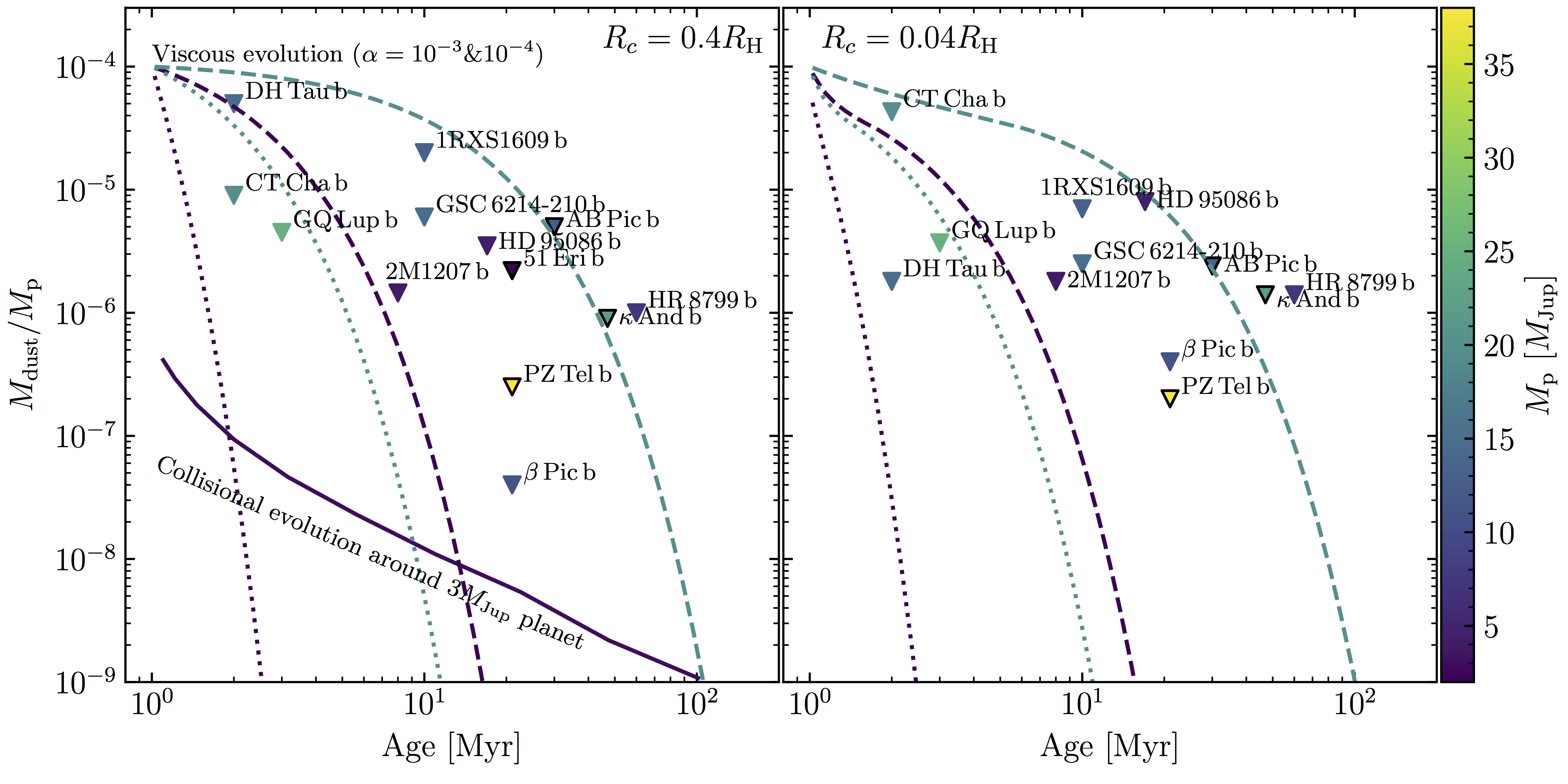

This paper presented new ALMA observations of four young directly imaged planets (PZ Tel b, AB Pic b, 51 Eri b, and κ And b) searching for the thermal emission from warm (10’s of K) dust in circumplanetary disks. Unfortunately they did not detect any emission above the background noise. Since the position of the planet is already known, they instead measured an upper limit. Using a relatively simple model of the disk, they converted this upper limit on the observed emission into an upper limit on the amount of dust in the disk. This is shown in Figure 1 along with previous measurements, which were also upper limits.

Using a second model, this time for disk evolution, the authors compared the mass upper limits to the amount of material expected to be remaining in the system given its age, assuming it started with a similar mass ratio to the moon systems in our solar system. These models are the curves in Figure 1. Even though the ages can be uncertain by up to ~50%, they found that most circumplanetary disks contain significantly less dust than would be expected for their age. This means that either these protolunar disks loose dust faster than the models predict or that the dust is still there but it has grown into larger objects which are not visible at millimeter wavelengths (particles do not efficiently emit light at wavelengths longer than their size). The second option is more likely. The authors go on to calculate a lower limit on the maximum size of particles in the circumplanetary/protolunar disks, given the previous upper limits on the observed mass (in particles <1 cm) and assuming a total mass and a distribution of particle sizes. These values are shown in Figure 2. For most sources this limit is >1 m, thus most of the dust mass must have coalesced into moonetesimals (which go on to form moons, like planetesimals go on to form planets).

Given the ages of these systems, moonetesimal growth seems to happen on a timescale similar to the planet formation timescale of ~10 million years. Thus, we need longer and more sensitive observations focused on the youngest giant planets to detect these circumplanetary/protolunar disks. It is amazing what we can learn from (and how important it is to publish) a bunch of non-detections!

Read the origional post at astrobites.org.